As an influential platform for photo-based and digital artworks, PHOTOFAIRS Shanghai has elevated many photographers from Asia-Pacific, embracing conceptual and experimental practices alongside modern masters and contemporary talents. In the latest Artist Voice, we speak to Shanghai-based M Art Center about the pivotal photographer Long Chin-San. In 2019, the gallery presented the exhibition Yuan Su (Elements), curated by Liu Tian, a Curator and the Deputy Director of the Visual Culture Center of China Academy of Art.

Long Chin-San

As one of the first Chinese photojournalists, Long Chin-San has been called “indisputably the most prominent figure in the history of Chinese art photography”. The title of this exhibition is implicitly contrasted with Euclid’s Elements and in response to the long-lasting ideology of “Chinese in essence, Western in practice” behind the work of Long Chin-San which is still active today.

“The camera is the machine, while art is earthed in idea and wisdom.”

Long Chin-San (1892-1995) was from Lanxi, the Zhejiang Province. During the 1930s, he came into the public eye as China’s earliest photojournalist. In the photography world, he is celebrated for a technique called “composite photography”, where he combines painting and darkroom techniques. He is considered the first artist to apply traditional Chinese painting principles to photography. In the introduction to the exhibition, the remarks on “composite photography” went as follows:

Long dedicated his life to promoting Chinese culture through his technique coined the “composite picture”, in which the elements of another world were shown. As he says, “They are carefully collected from the universe. The empty dark room provides white space to connect different elements. By knowing and observing but staying obscure, there is more to the picture.”

© Exhibition View of Elements: Selected Photographs of Long Chin-San, 2019. Courtesy of M Art Center (Shanghai)

Long got to interact with many local and foreign artists. Chang Dai-Chien called him San Ge (older brother) and often talked to him about picture composition. Qi Baishi, Huang Binhong, Ye Qianyu, Yu Youren saw him as a close friend. Furthermore, he had a good relationship with foreign master photographers, such as Man Ray, Imogen Cunningham and Ansel Adams.

Long experimented with shadow photography. He put transparent, translucent and opaque objects directly onto photosensitive paper to produce an aesthetic halfway between Chinese freehand brushwork and cubism. It was found that he tried to increase the light levels in the highlights of his works, which was quite different from the softer tones used by Western photographers.

Long advocated learning skills from the West. However, he was always strongly connected to the spirituality of traditional Chinese paintings in terms of artistic philosophy. He planned the photograph by using the six principles of Chinese painting, which are: Spirit Resonance (vitality); Bone Method (the way of using the brush); Correspondence to the Object (the depicting of form); Suitability to Type (the application of color); Division and Planning (placing and arrangement) and Transmission by Copying (the copying of models). This was thought to produce an image of the highest quality.

© Exhibition View of Elements: Selected Photographs of Long Chin-San, 2019. Courtesy of M Art Center (Shanghai)

PF: Do you think Long’s works are pioneering or classic?

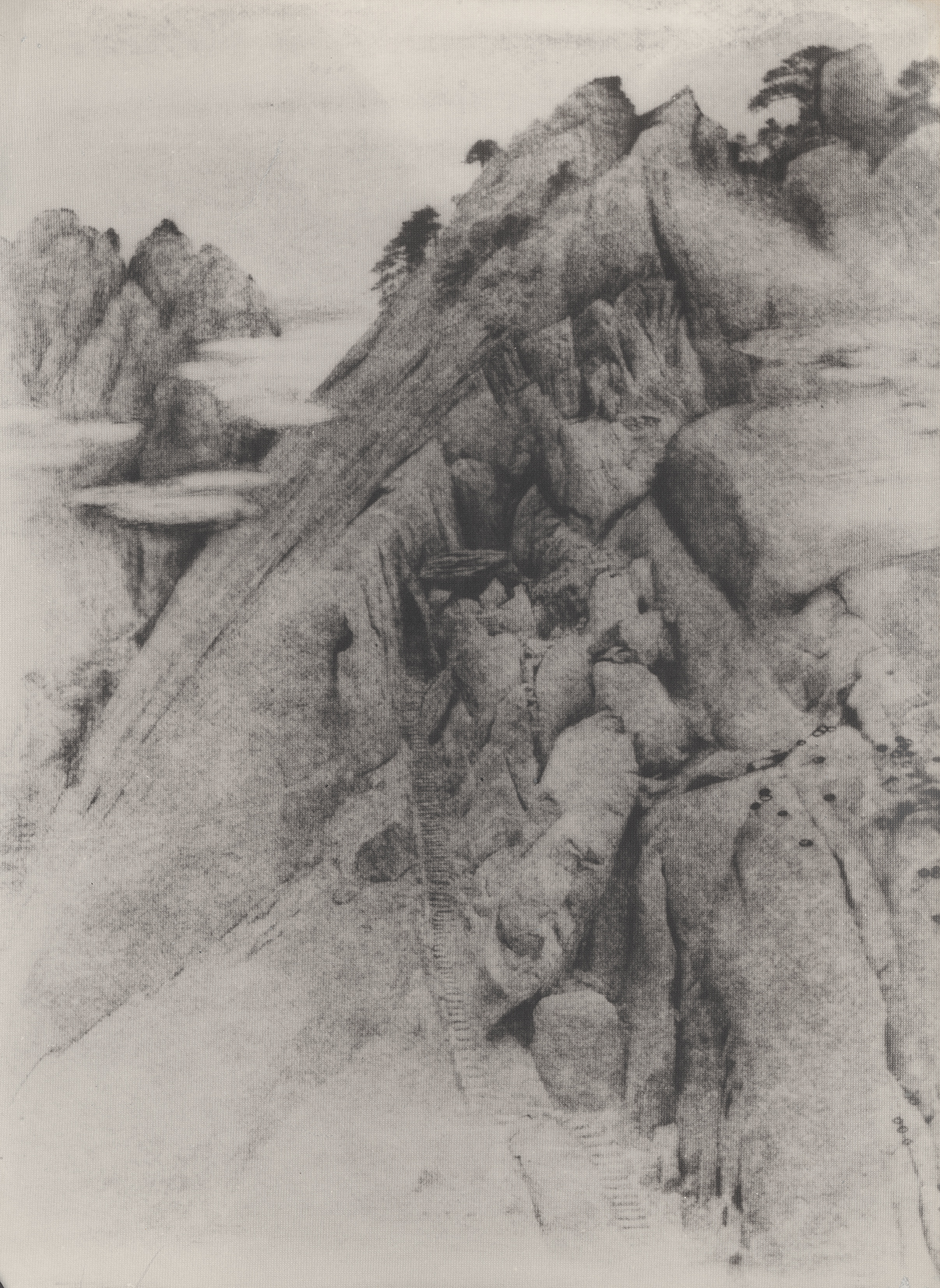

M Art Center: Well, they could be either. For example, in his work ChangJiang (Yangtze River) in 1930, he made an extraordinary contrast between black and white despite the light and even drew a river flowing to the sky in acrylic paint. That is pretty surreal! While speaking of his classic works, it’s clear he tried to transfer the landscape of the Northern Song and Five Dynasties – an era of political upheaval and division back in ancient China – to his photographic works.

© Long Chin-San, Walking Alone, Created in 1965, Reproduced in 2019. Courtesy of M Art Center (Shanghai)

PF: Does “composite picture” have much of an impact on the development of photography? What is the relationship between photography and painting in this technique?

M Art Center: We can see Long’s insistence on the unity of photography and painting in his “composite picture” style. He started to use a painterly approach on the negatives and he only created images of China, and never publicized any non-China-related works. He experimented a lot in the darkroom and tried out different materials.

© Long Chin-San, Parking at Moonlit Night, Created in 1960, Reproduced in 2019. Courtesy of M Art Center (Shanghai)

PF: Apart from Man Ray’s rayograph and cubism, what were some other Western artists or movements that had an effect on Long Chin-San’s practice?

M Art Center: Mr. Long did not copy Man Ray. He began to use the photogram in his practice during the early 1950s, as we see in Mosquito and Flower (1952) and Pet (1956). Actually, these two artists, one from the East, the other from the West, simultaneously played the same interesting “game” as if they had one heart.

© Long Chin-San, After the Tang’s Master, 1936. Courtesy of M Art Center (Shanghai)

PF: As the contents of the photograph/image are getting more extensive and complicated, will Long’s works give us some new way of interpreting the world?

M Art Center: Mr. Long’s works can be enjoyed from different perspectives. If they are studied, a lot of contemporary images can be found because art itself means endless possibilities. However, not only art, but also our accessible resources and environment have become more complicated. Therefore, Long’s works bring our heart back to its natural habitat.

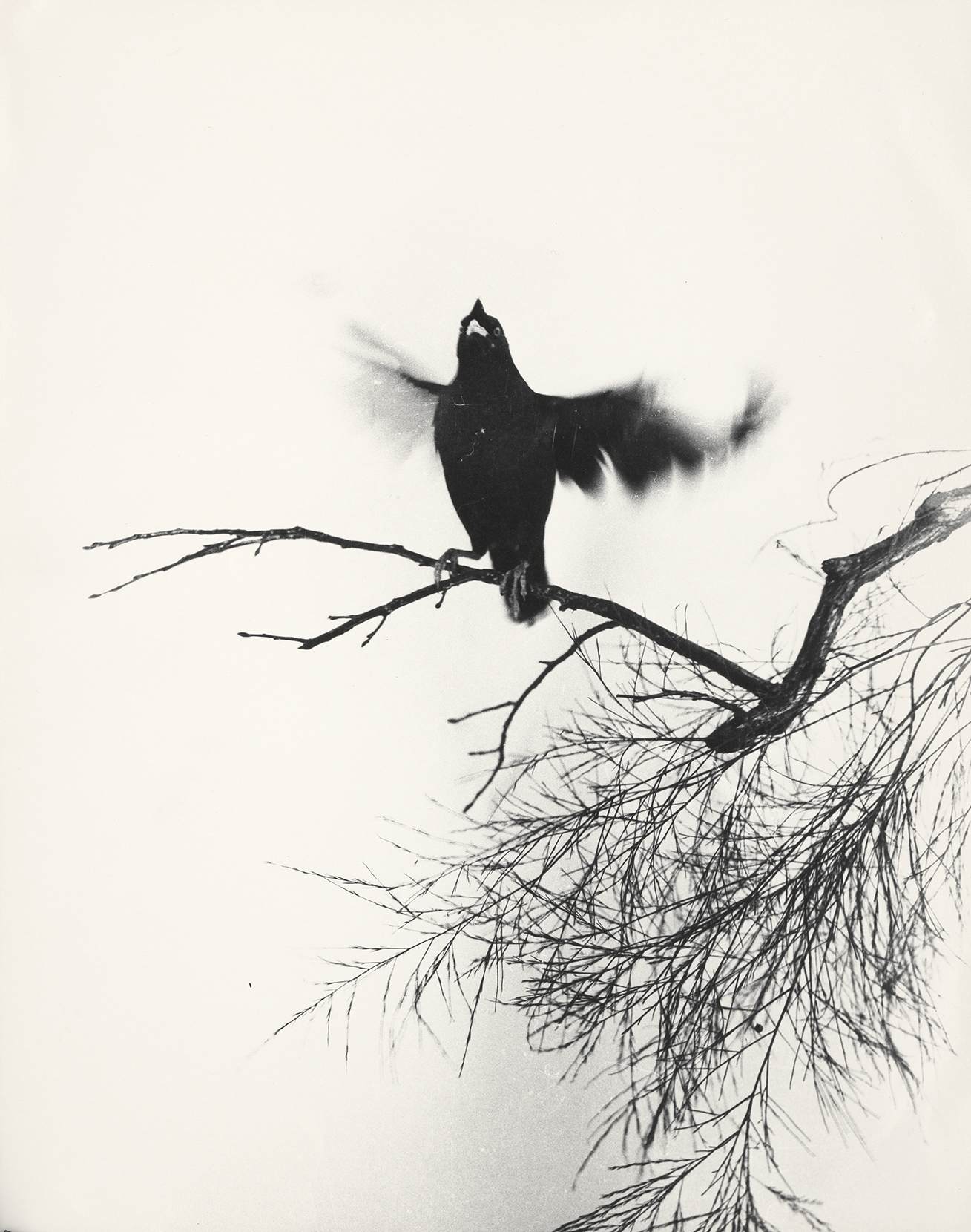

© Long Chin-San, Taking Off, 1955. Courtesy of M Art Center (Shanghai)