The Fifth Lanzhou International Image Biennale was launched in Lanzhou in early July under the theme “A Room with View: Chinese Landscape Photography in Contemporary Context”. The Biennale included six sections: the main exhibition, collateral events, invitational exhibitions, an institutional curatorial unit, the inaugural Art Book Fair in Lanzhou, and an academic forum, which were held simultaneously at the Yan’er Bay Contemporary Art Museum, the Gansu Art Museum in Lanzhou, and various other venues. Furthermore, this exhibition provides an opportunity to showcase the Northwest region’s unique photography and promote and explore the dynamic regional imagery.

Exhibition View of The Fifth Lanzhou International Image Biennale, 2023.

The vast Northwestern region of China, including Shaanxi, Ningxia, Gansu, Qinghai, Xinjiang, and western Inner Mongolia, has always been incredibly captivating throughout the history of Chinese photography. In the early 20th century, the exploration of the Northwest area was greatly aided by photography practices. Places like Dunhuang and Loulan were visited by western missionaries, botanists, and Chinese intellectuals. And the photos taken during those visits contributed greatly to the anthropological preservation of the region’s distinctive landscapes, geographic ecosystems, urban and rural sceneries, social lives, and ethnic cultures. One notable figure from this period is Zhuang Xueben, a renowned photographer on the Chinese Mainland under the Republic of China’s rule. His work not only holds historical value but also exhibits mesmerizing artistic merits that fall under the category of anthropological imagery.

© Zhuang Hui, Qilian Range, Redux-11, 2015. Courtesy of GALLERIA CONTINUA (San Gimignano, Beijing, Les Moulins, Habana, Roma, São Paulo, Paris, Dubai)

During the 1980s, a collective of photographers, led by Hou Dengke and Hu Wugong, known as the “Shaanxi Photography Group,” began producing documentary-based works that expressed their own viewpoints. Their influence gave rise to a new generation of talented photographers in the Northwest region, such as Li Qiang and Cong Feng, who brought their own unique perspectives to enrich people’s perceptions of this area. After 2000, the Northwest region provided even more opportunities for observation and experience, attracting not only local artists and photographers but also attention from outside. Artists like Zhuang Hui, Zhao Zhao, Zhang Lanpo, Wang Yishu, Mu Ge, Luo Dan, Zhang Kechun, Lin Shu, Ta Ke, Zhang Xiao, and Ma Hailun have all played an indispensable role in shaping the artistic landscape of the Northwest and have become prominent figures in Northwest photography.

In addition to the traditional visual representations associated with the Northwestern region, such as deserts, plateaus, and mountains, contemporary Northwest photography explores profound themes including personal memories, the transformation of urban and rural areas, and cultural identities. Photographers are attempting to incorporate real-world concerns with literary narratives and expressions in their creations. In this context, the Fair has carefully selected works from nine artists whose creations provide viewers with a glimpse into a more dynamic and imaginative Northwest.

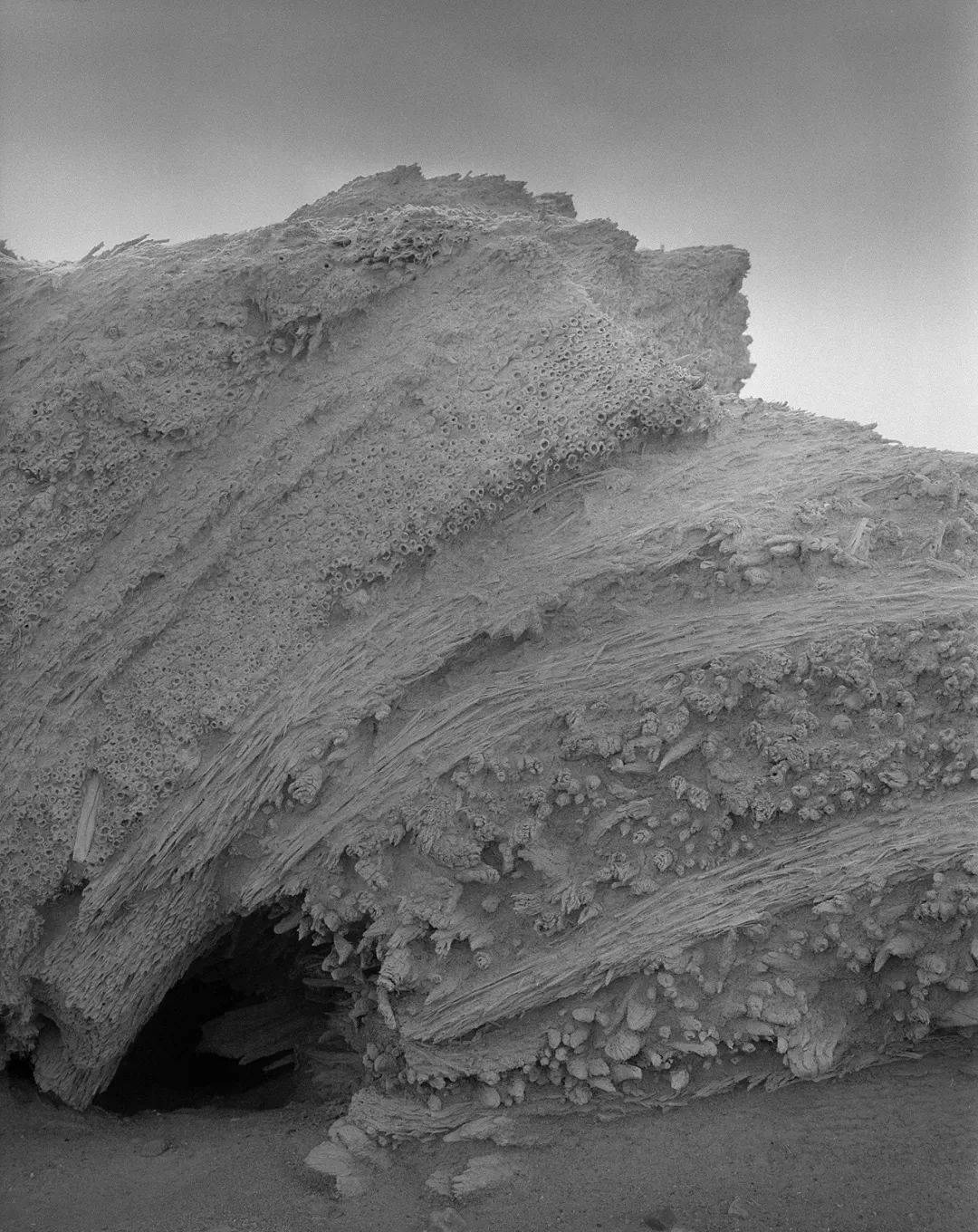

Di Jinjun

Born in Shanxi, China, in 1978, Di Jinjun currently resides and works in Beijing. He is a pioneer in mainland China of using wet-collodion processing with black glass for artistic purposes. His exceptional work has earned him multiple awards, including the TOP 20 Chinese Cutting-Edge Contemporary Photographers and the Silver Award of the Asia Pacific Photo Forum (APPF) for emerging photographers.

Light of Silk Road

“The Hexi Corridor, commonly known as the ‘throat’ of the Silk Road, holds immense historical importance as a key segment of the ancient trade route. It spans approximately 1,000 kilometers along the Kunlun Mountains and ranges in width from a few kilometers to nearly a hundred kilometers, forming a long and narrow plain that resembles a corridor. Its unique geographical location has made it a vital and highly valuable part of the Silk Road. The corridor spans enormous deserts and passes through towns like Liangzhou, Ganzhou, Suzhou, Shazhou, and Guazhou, ultimately connecting ancient China to the rest of the world and promoting its civilization and culture throughout the world.

Charles Wheatstone invented the stereoscopic camera in 1838, Archer introduced the wet-collodion process in 1851, and George Eastman created the film in 1885. These innovations hold an irreplaceable place in the history of photography and have had a significant impact on how we create images today.

Photographers travel over a thousand kilometers in the Hexi Corridor. They gently poured developer solution across aluminum plates in an attempt to record the passage of time, capturing the people, terrain, and windswept sand dunes of the vast Gobi Desert. The presence of a small aperture in the lens of the stereoscopic camera allows light to freely pass through and project onto the film base, which in turn forms a light trail during exposure. This is a process when light unrestrictedly intervenes with precise composition, resulting in two outcomes on the film: controllable visual effects and unexpected underlying images.”

—Di Jinjun

Zhang Jin

Zhang Jin was born in Sichuan, China in 1978 . He currently lives and works in Chengdu. Zhang Jin is the winner of the 2012 Three Shadows Photography Award. His works are collected by the White Rabbit Gallery in Sydney and the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre in Beijing.

Another Season

“I need to walk alone along the eastern section of the ancient Silk Road, from Chang’an to Yangguan. Not only because it was Buddhism’s in-road to China, but also because of my enthusiasm for the grand desert and a chance to encounter an unknown landscape. Here there is silence, with springs in the woods and mist. There are traces from ancient civilizations, and explorations fit for a seer. There is also nature and life, which continue to exist everywhere regardless of the changes in dynasty or nation over time, with strength born from basic instinct. Season after season, it runs its cyclical course. Like a pilgrim, I position myself in the landscape, villages, and temples, to explore the spirituality of the inner self, to embrace ineffable adventures, and to revisit various accounts of the Silk Road found in classical records. I try as much as possible to remove traces of time and history from my photographs. I hope to place current time at a distance, in order to let the photograph connect with the past of the ancient Silk Road and its future.”

—Zhang Jin

You Li

Born in Shenyang, Liaoning, in 1978, You Li gained recognition in 2010 when her work, Latitude of Silence, earned her the Best Newcomer Award at the Southern Documentary Photography Exhibition and the Outstanding Artist Award at the Lianzhou International Photography Festival.

Kashgar

“In 2007, I started shooting Latitude of Silence. And I’ve visited various northern places a lot since then. I made my first trip to Kashgar in the fall of 2010. At that time, roughly half of the old Kashgar city, mainly the residential districts, had been removed and rebuilt. The Gaotai residential neighborhood and the Kashgar Old City Scenic Area were contracted by the government and tourism businesses and, as a result, were largely preserved. Other residential districts were rapidly undergoing demolition and reconstruction.

In the spring of 2011, I returned to Kashgar. The construction was put on hold in February and March. However, starting in April, the main streets, including the vital commercial streets and cultural centers within the old city, such as Areya Road and Wusitangboyi Road, were included in the redevelopment plans and began to be demolished.In May, the Gao Tai residential area ceased the sale of tickets to tourists, citing the necessity for maintenance. A number of buildings on the southern side of the Gao Tai residential area were demolished.

I believe that the demolition and reconstruction of Kashgar Old City had an impact beyond the disappearance of buildings. It also resulted in the loss of a distinctive, antiquated atmosphere. Even the subtle changes on the streets were proof that assimilation was being done on purpose. Throughout my stay there, I saw that this change also included people’s needs for more readily available comfort. But for certain well-known causes, what ought to have been meticulous, specific, and individualized adjustments became large-scale demolitions and reconstructions. I can only say that it is time for the ancient city to say goodbye. One day, people, regardless of their ethnicity, will look back on everything that has to do with the ancient city and feel regretful, hurt, and scarred. Many scenes captured in the photographs no longer exist today, and it seems as if they never existed at all. They are barely captured before history flips them over the next day. Even the thought of how Xinjiang, despite its size, fails to coexist with the tiny ancient city is sad.”

—You Li

Li Wei

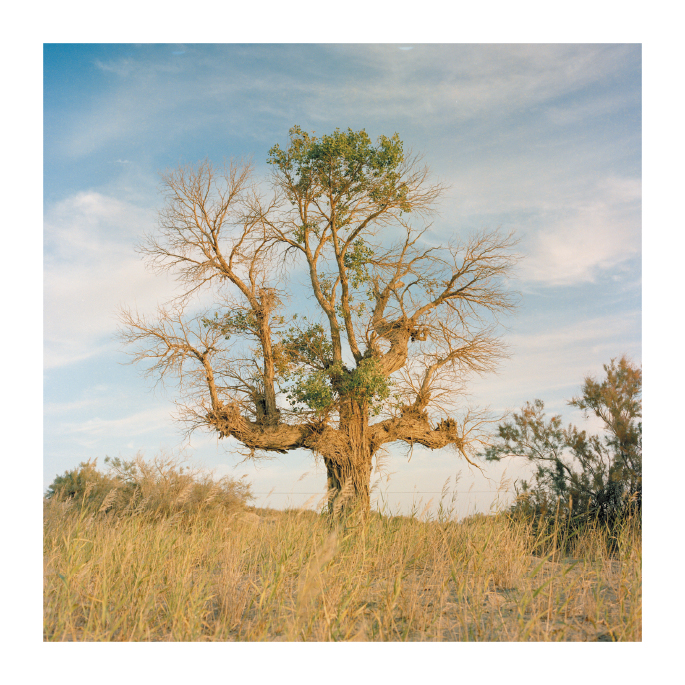

Li Wei was born in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China in 1976. He currently lives and works in Beijing. His work has been exhibited at the 2020 Head On Photo Festival, Sydney, Australia; the 2019 Lanzhou International Photography Biennale, Lanzhou, China; and the 2013 Beijing Photo Biennial, etc.

The Good Earth

“I was born in Hohot, Inner Mongolia in 1976. Lying on the north border, Inner Mongolia is the largest grazing region of China. Han and Mongolian people live off this land. My affection for my hometown made me think of this land. I’ve been photographing Inner Mongolia during my travels since 2008. These photographs are of the people and their everyday life in this borderland region. On the grand grassland, the traditional nomadic lifestyle was influenced by the impact of modernization. Some herders do not live in the yurts anymore, instead, they have settled in towns. Some young people would rather dress themselves more fashionable ,only old mongolian people wear mongolian dress now.”

—Li Wei

Qiu

Born in Pingyuan, Guangdong, in 1974, Qiu currently resides and works in Guangzhou. He has published several works, including Miasma & En Ning (2017), Chronicle (2009), The Daydreams of Qiu (2008), and Wuxu Mountain (2022).

Wuxu Mountain

Wuxu Mountain is a sacred place where divine spirits dwell among the majestic mountain ranges, vast fields, and lush trees. Rivers, lakes, guiding birds, trees, lightning, sunlight, deserts, Yinshan Mountain, the Great Wall, wild horses, mountain ranges, twilight, foxes, the moon, glaciers, Buddhist grottoes, tunnels, snowy landscapes, heavenly lakes, ruins, tombs, remnants of Buddha statues, bones, poplar trees, legends, and more—all of these elements form the Wuxu Mountain.

Qiu’s creation of Wuxu was driven by his desire to uncover ancestral traces within the northern regions. It is a visible yet unreachable place, reflecting the ancient history that lingers in the present. This ethereal place emerged when pieces of time and space collided. Only through remnants scattered across the mountains can one catch a fleeting glimpse into a bygone era.

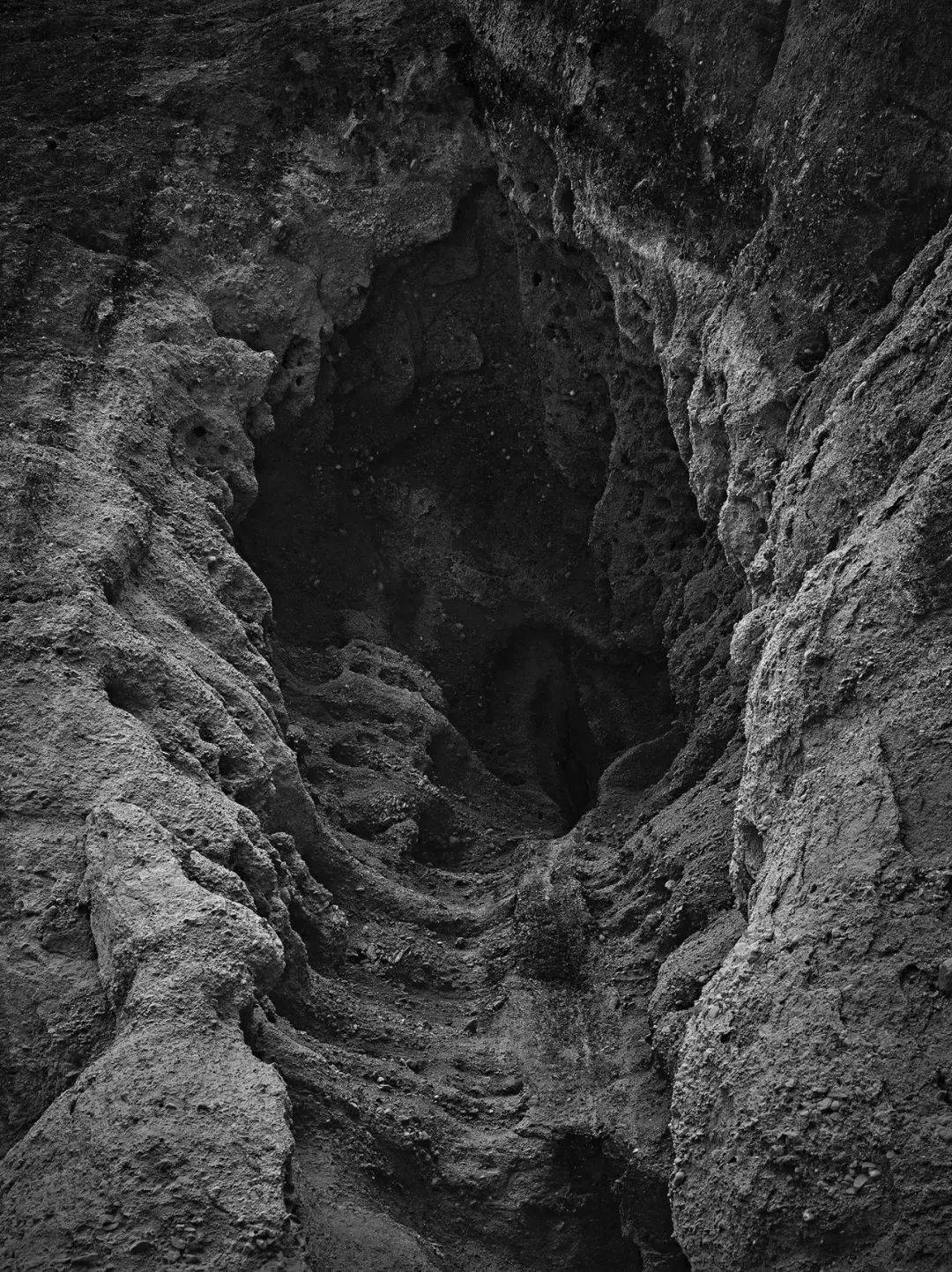

Chen Hua

Born in Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, in 1983, Chen Hua is a photographer, screenwriter, and filmmaker. His works focus on the theme of history, culture and memories, which were shortlisted for the Hou Dengke Documentary Photography Award, TOP20 China’s Contemporary Photography Exhibition, etc.

In Chang'an

“The city where I live in, now called Xi’an, has an ancient name, Chang’an.

It has a very brilliant history,for it had been set as the capital by thirteen old dynasties lasting one thousand years. Once, Chang’an, like Rome, Jerusalem or Xanadu, was one of the most important cities in the ancient world. However, all its glory has now become the ruins buried in the soil. Civilization continues to be established and continuously destroyed. Under this land, there are many layers of ruins. For thousands of years of war and famine, it completely bid farewell to the past glory.

This city is composed of two parts: the present and the past. The palaces and tombs of the emperors two thousand years ago are juxtaposed with the blocks and villages we live in now. In this city, the past and the present are magically reunited.Poetry, religion and history, numerous war and famine are mixed here, accompanied by destroying and rebuilding of this city. All paths in this city lead to a site or ruins.”

—Chen Hua

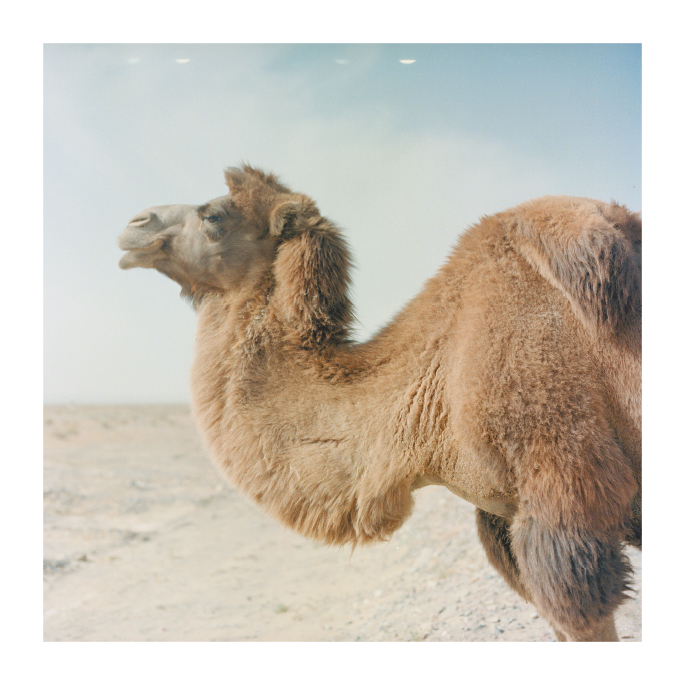

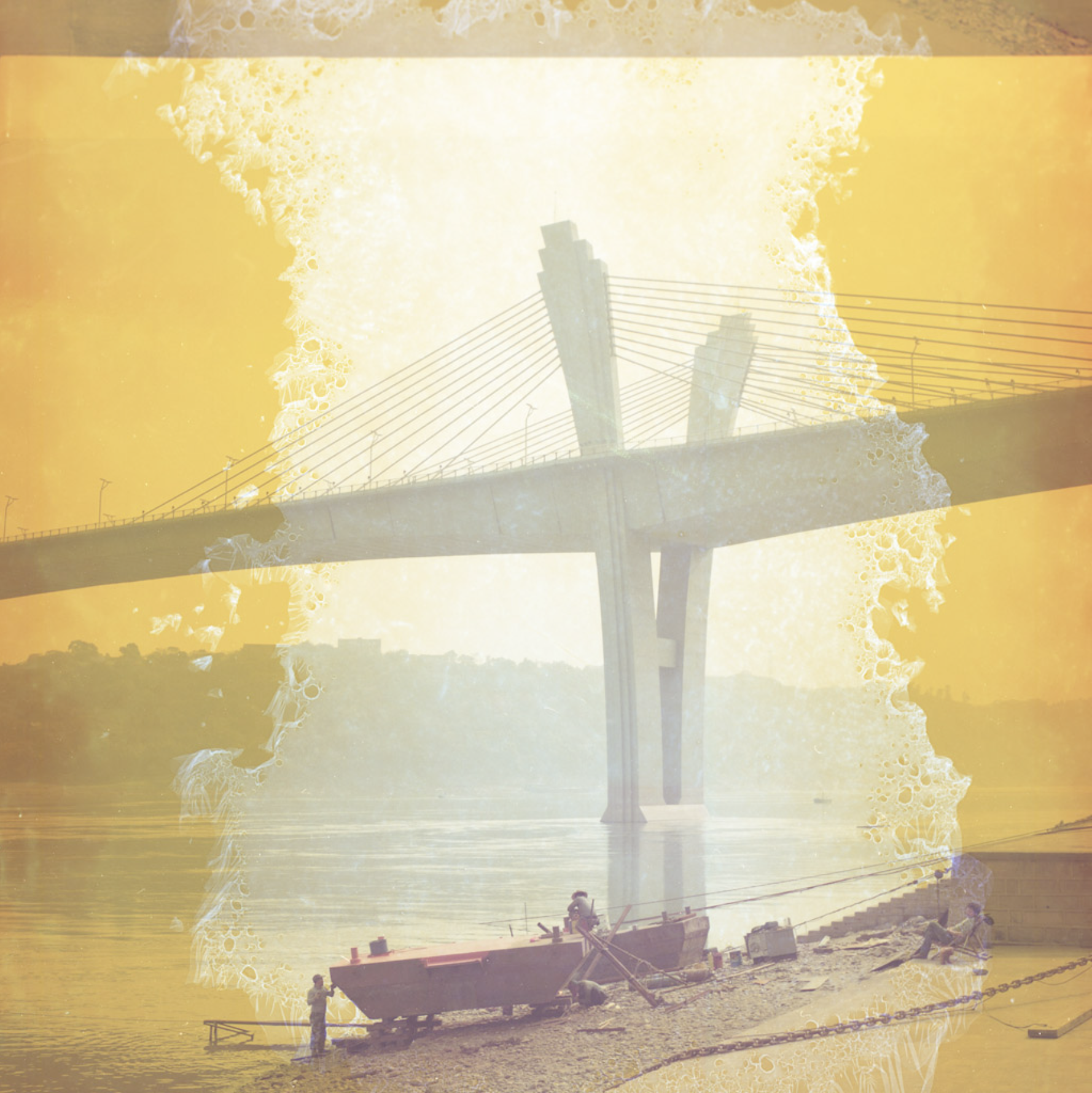

Zhang Boyuan

Zhang Boyuan was born in Urumqi, China in 1993. He currently lives and works in Beijing. Zhang strives to explore his hometown and self-identity through photography. His ongoing project, My Tarim, has won numerous awards and been exhibited worldwide, such as London, New York, Rome, Tokyo, Taipei amongst others.

My Tarim

“’Hometown’ is a word that being rarely used in Chinese dialog. It always comes with the context of someone bearing something, like distance, taste, faces, temperature, and regret. Put them together, the other side of the equal sign could be ‘memory.’ The Tarim Basin is an area where almost left no memory on me since I was born, hence the sense of rootlessness and the confusion of my identity made my abroad time even more self-doubting and homesick.

The extent to which I can connect with this uncompleted hometown can only be known if it is completed. Going south to sense the root of the landscapes and the flavors was my only option. For me, photography is beyond a medium to record the scenes, it is a storage system that closes to ‘memory.’ For more than two years of extension in the Tarim Basin, I managed to use photographs to create a ‘memory library’ for my hometown. To complete one’s hometown, one needs to ‘choose it as a hometown’ in the first place.

I was looking at the eyes of the person who had looked at the discoverer of Loulan’s Ancient City Ruins whilst hearing the stories from him about his ancestors’ adventures a hundred years ago. I have seen the empty eyes of the Loulan Beauty that have been sleeping in the Taklimakan for more than 3,000 years, with her secrets being sealed in time and sands. The portrait of each sheep leads to a dining table, the camel that without a bell leads to a remote far away. ‘My Tarim’ is the Tarim that only belongs to me, to tell the narrative of life and death is her destiny.”

—Zhang Boyuan

Kurt TONG

Kurt TONG was born in Hong Kong, China in 1977. His series Dear Franklin was awarded the Prix Elysée in 2021. The photobook of this series was also one of the top ten recommended photobooks by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 2022. TONG’s works revolve around personal projects exploring his Chinese roots and understanding of his motherland.

Sweet Water, Bitter Earth

Kurt TONG was born in Hong Kong, China. He spent his childhood in the United Kingdom before returning to Hong Kong. His father originated from an impoverished family of fishermen from Xiangshan who immigrated to Hong Kong at an early age. On the other hand, his mother was from a well-off family of landlords in Guangzhou who later relocated to Hong Kong to evade persecution.

TONG’s initial perception of mainland China was shaped by the Japanese documentaries and television shows he watched during his childhood, particularly “The Silk Road”, as well as various photographic pieces. To validate or challenge these preconceived notions, he decided to retrace the routes taken by his parents through Hunan, Sichuan, Yunnan, Qinghai, Gansu, Heilongjiang, and other regions. In his work, Sweet Water, Bitter Earth, the themes of father and mother, as well as water and land, are intricately woven together to create a compelling story about family and memory. The photographs in the book serve to enhance the written text, much like water nourishes the land.

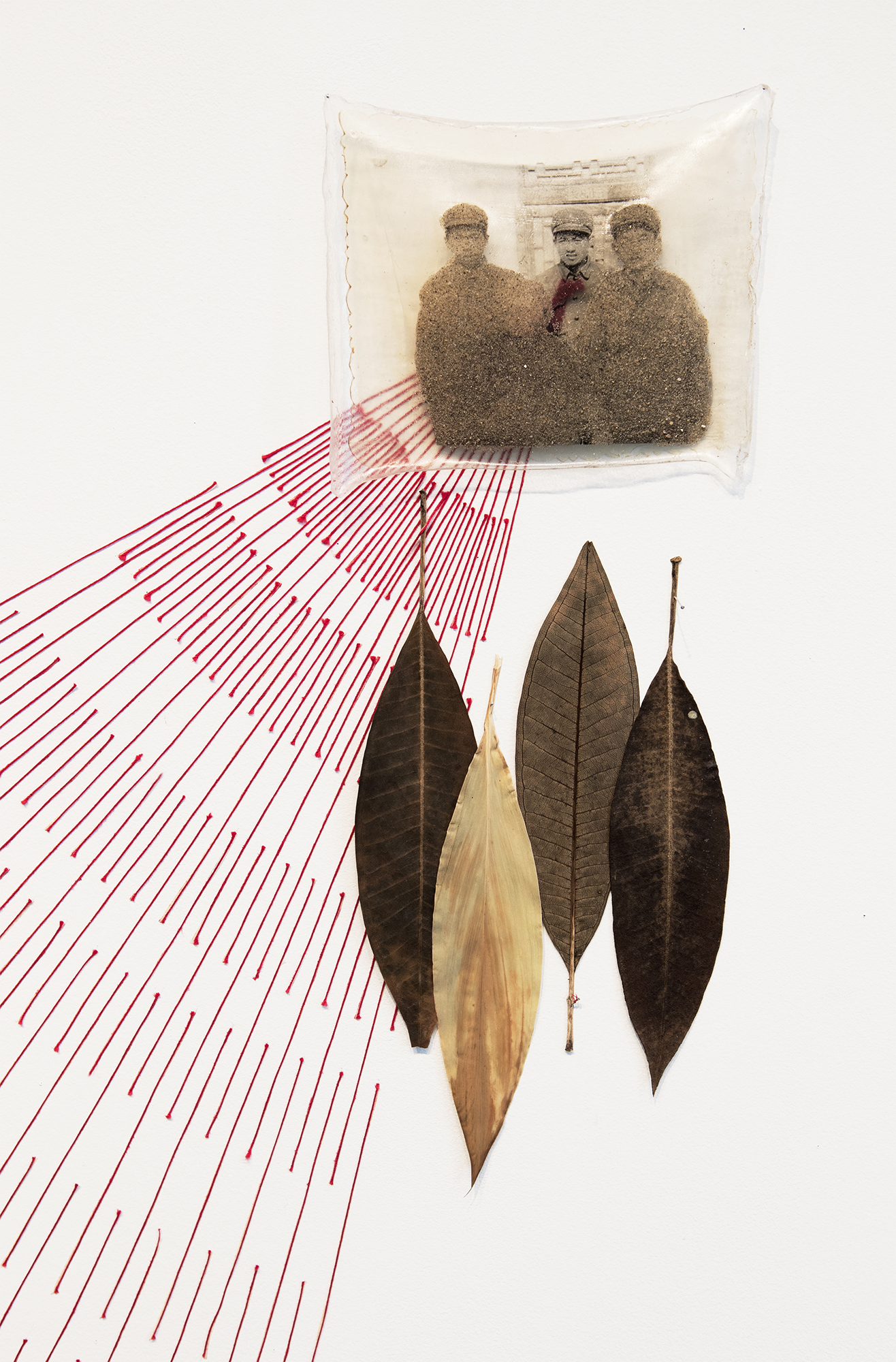

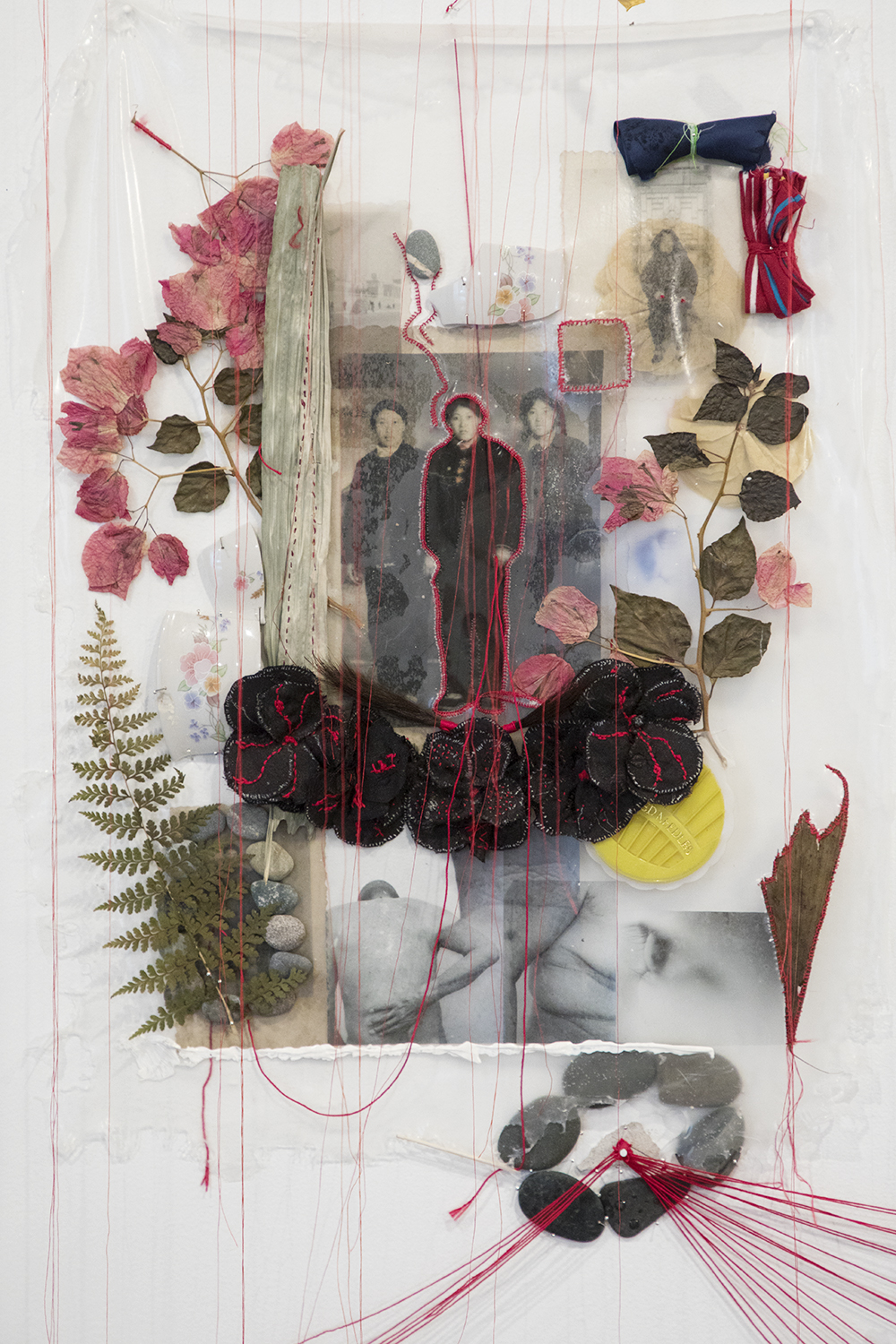

Wang Jia

Born in Lanzhou, Gansu Province, Wang Jia won the “Redpoll Trophy” Best New Artist Award at the 9th Dali International Photography Exhibition for her work, Residual Imprint.

Residual Imprint

Wang Jia’s artistic creations delve into the profound influence of Chinese traditional culture and the enduring effects of family trauma on individuals. Through her works, she delicately recreates and explores themes such as history and memory, survival and mortality, as well as identity and self-discovery.

Residual Imprint is Wang Jia’s representative work since her exploration of this subject in 2019. All the objects displayed in the artwork are from her personal memories: old clothes worn by family members, medicine pills taken by loved ones, old family photos, pebbles from the Yellow River, the quilted jacket she wore as a child, and old photos on various objects. These personal imprints from Wang Jia not only connect the historical changes of a family but also document the developments of an era. Through her personal-experience-oriented artwork, Wang Jia is now exploring how to use materials, textures, touch, weight, and “visual empathy” to grasp and reflect on the relationships and meanings between individuals and families, absence and existence.