Taca Sui, born in Qingdao in 1984, is one of the representatives of the Chinese mid-career photographers. He studied at the China Central Academy of Fine Arts and the Rochester Institute of Technology in the United States. Unlike other Chinese contemporary photographers of his generation, Taca’s work has its roots in Chinese traditional literature and focuses on the exploration of relics and the remaking of memory. Taca is influenced by both classical Chinese ink painting and Western modern art. He’s also influenced by the pioneering photographer Zhuang Xueben, who, in the early 20th century, conducted extensive anthropological research in ethnically diverse regions like Sichuan, Gansu, Qinghai and Yunnan. Zhuang’s research focused on the daily life, religion, clothing, local specialties and geographical environment of ethnic minorities such as Qiang, Tibetan, Yi, Tu, Dongxiang, Mongolian, Baoan and Naxi, leaving behind a significant number of photographs, reports and diaries that hold research and artistic value.

Taca Sui

“Photography can accomplish what our naked eyes cannot. It captures a moment that will soon pass, using the present to document vanished historical traces.”

Taca shares a similar practice. He tracks the trail of ancient civilizations and documents them through photography, a process inseparable from literature studies and field research. His first solo exhibition in collaboration with Three Shadows +3 Gallery focuses on his five-year investigation into Grotto Heavens, a concept derived from Taoism. Prior to this, his series of works titled Odes, which was inspired by The Book of Odes, also took nearly five years to complete. It involved extensive research and investigation into the locations mentioned in these ancient folk songs. In general, a thorough literature study and field investigation are Taca’s standard procedures when it comes to photography. However, what sets him apart from anthropologists or literary scholars is that he views photography as more than just a means of documenting, translating, and understanding present or ancient books. Instead, photography serves as a key that unlocks the past and connects different worlds of different times and spaces.

Taca is often jokingly referred to as the ‘tomb photographer,’ as his works possess a desolate yet timeless beauty and lingers on the blurring boundaries between the past and present, reality and fiction, artistic expression and academic inquiry. His works have been exhibited in renowned institutions such as the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, the Three Shadows Photography Art Centre, and the Zhejiang Art Museum. Among them, Odes is included in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2014. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, the CAFA Art Museum, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art have also included Taca’s work in their collections.

© Taca Sui, The Hub of Wheel, from Chapter ‘The Journey of Wei Wan’, 2022. Courtesy of the artist & Three Shadows +3 Gallery (Beijing, Xiamen)

As the exhibition Land of Solitude: New Works by Taca Sui draws to a close, we are fortunate to have the opportunity to invite this self-proclaimed visual archaeologist to speak about his years of work and his distinctive artistic aesthetics.

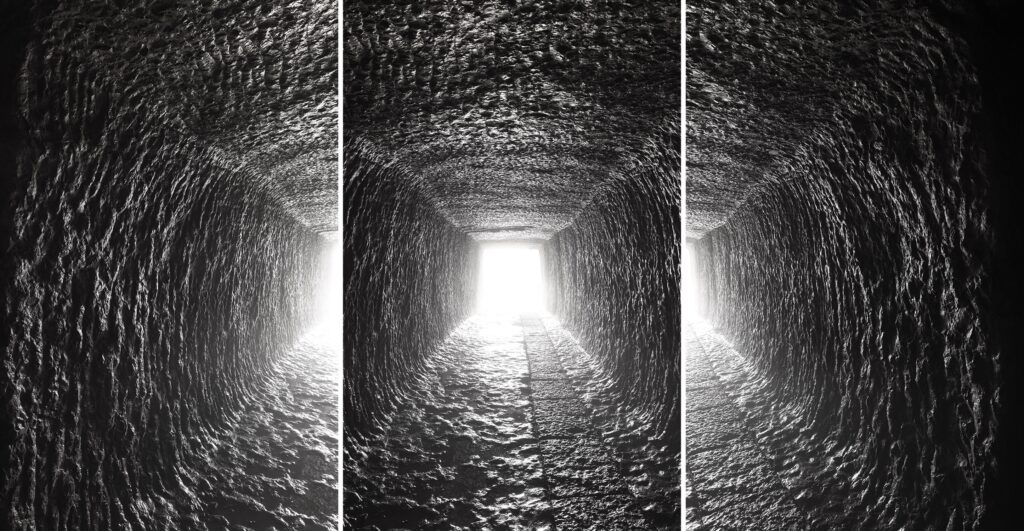

PF: Why are you interested in the concept of Grotto Heavens?

Taca: Actually, I became interested in the theme when I was working on Steles. Once, I unexpectedly entered a cave in Jinan called Longdong, a cave that Huang Yi had once visited. I was alone in the cave. And suddenly, my phone died, leaving me in complete darkness. My sixth sense appeared to come to life at that precise instant when all five of my senses were blocked. I can still clearly recall getting chills all over. Later, I came upon a description of the same emotion in Zhang Yanghao’s Record of Longdong Mountain from the Yuan Dynasty. The fear of darkness is deeply embedded in the human psyche, it’s almost instinctive. This sparked my curiosity about the origins and evolution of this intriguing concept known as Grotto Heavens. I wondered when and under what circumstances it first appeared and how it changed over time.

© Taca Sui, Cave in Wudang Mountains, from Chapter ‘The Immortal Land’, 2018. Courtesy of the artist & Three Shadows +3 Gallery (Beijing, Xiamen)

PF: You have shown a keen interest in historical relics in both your most recent pieces, shown in this exhibition, and your earlier works like Steles and Odes. Does your theme ever shift in your practice?

Taca: I am always focusing on literature, primarily the classics. And my interests have always centered around historical texts or certain aspects of ancient people, events, and objects. I am less interested in exploring the present. My first project took around four to five years to complete; it started in 2009 and ended in 2013. I looked into the places mentioned in The Book of Odes, such as mountains, rivers, ancient sites, and capital cities, and took pictures of them.

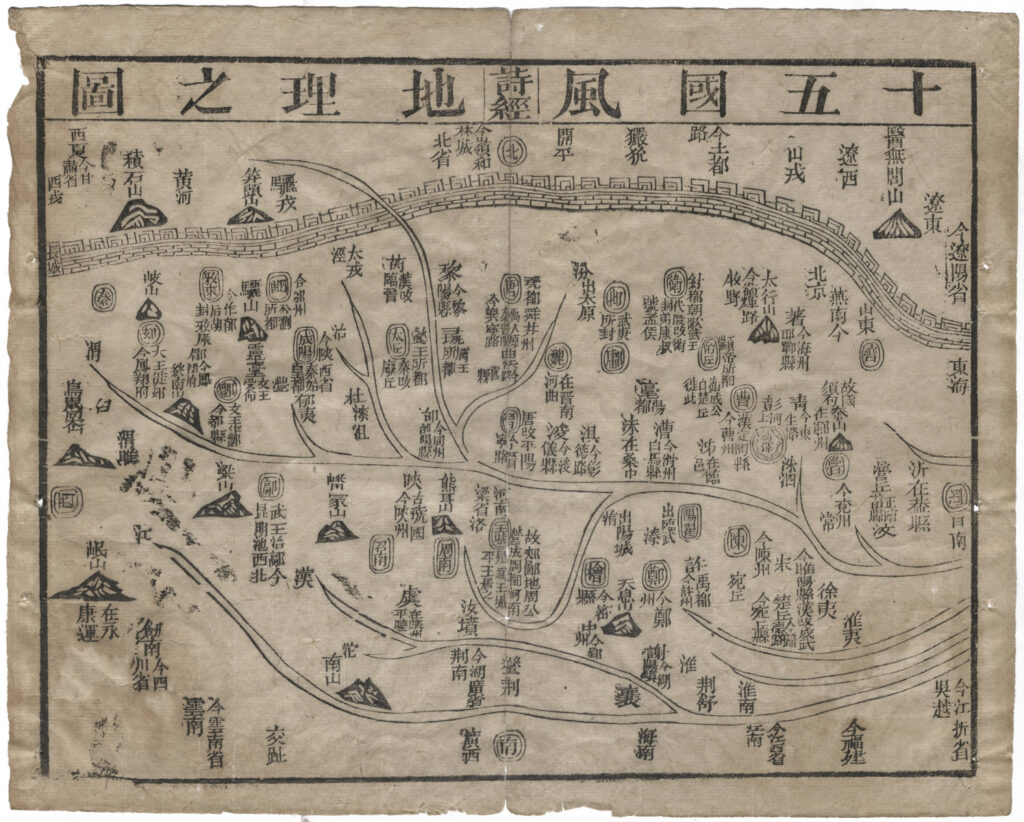

The map referenced in Odes. Courtesy of the artist

The Book of Odes is unique among other pre-Qin texts since it provides a substantial record of everyday life, including songs written by common people. This is why it brings you a comforting familiarity, which evokes feelings of tranquility, liveliness, and even solitude and sorrow that are conveyed in the poems. It is quite natural then to fantasize about the magnificent lands that inspired such beautiful poetry, and wonder what they were like in that time and how they appear today, after two millennia have passed. Therefore, I decided to visit these places and experience firsthand if there are still any traces left behind from 2,000 years ago. This is how Odes came to be. And naturally, my other projects followed a similar process – developing from historical literature.

© Taca Sui, Odes, 2009-2013. Courtesy of the artist

PF: What is the relationship between literature/culture and photography/images in your work?

Taca: I have been wondering about a similar question as well, regarding the lingering soul or spirit of the ancient civilization. It’s fascinating to note that this idea has become quite popular since the invention of photography. Many artists in different countries have engaged in similar endeavors.

Can the land that witnessed certain events carry those memories? The past is intangible yet omnipresent, and all the details on the land possess the power to shape our visual understanding and experiences. Historical landscapes and the various descriptions associated with them await our reinterpretation and reimagining. The past still exists today. It has just taken on an ethereal form, but everything in our surroundings hints at its presence. For me, photography serves as the most effective means to point out these traces and remnants.

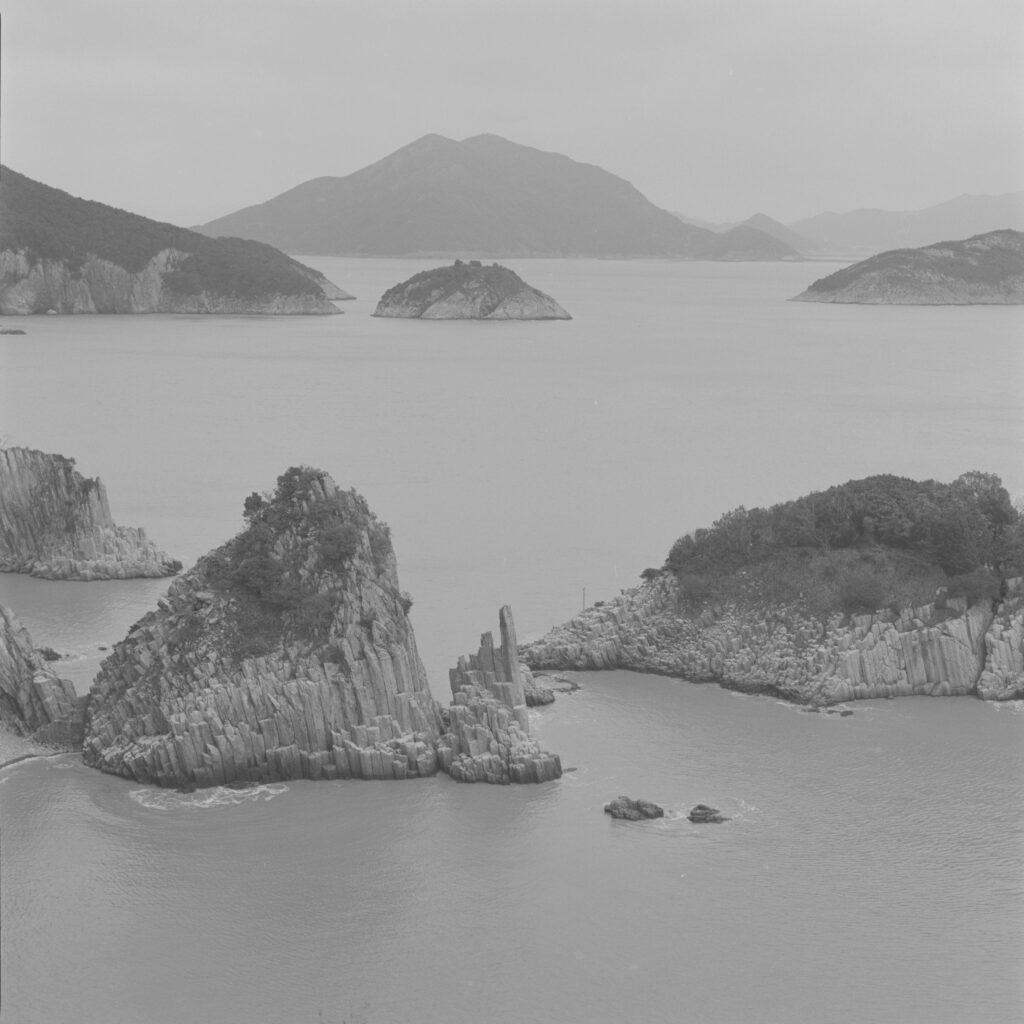

© Taca Sui, The Rock of Northern Great Mountain, from Chapter ‘The Journey of Wei Wan’, 2022. Courtesy of the artist & Three Shadows +3 Gallery (Beijing, Xiamen)

PF: If the audience is unfamiliar with the literature or the culture, for instance, if they haven’t really studied The Book of Odes, Grotto Heavens, or Huang Yi’s Stele Records, from what perspectives can they understand your works?

Taca: Andrei Tarkovsky believed that when people watched his films, their direct emotions were far more important than any theory or analysis. I understand his thinking. and think the same principle applies to photography. Photography can accomplish what our naked eyes cannot. It captures a moment that will soon pass, using the present to document vanished historical traces. Viewers can later be inspired by those photos and develop their own interpretations of events. I wonder if this sort of imagination is purely personal, or if it is shared by others from similar cultural backgrounds. Perhaps this question should be posed to Jung, as it touches upon the collective unconscious.

© Taca Sui, The Lord of Heaven, from Chapter ‘The Eight Lords of Qi State’, 2022. Courtesy of the artist & Three Shadows +3 Gallery (Beijing, Xiamen)

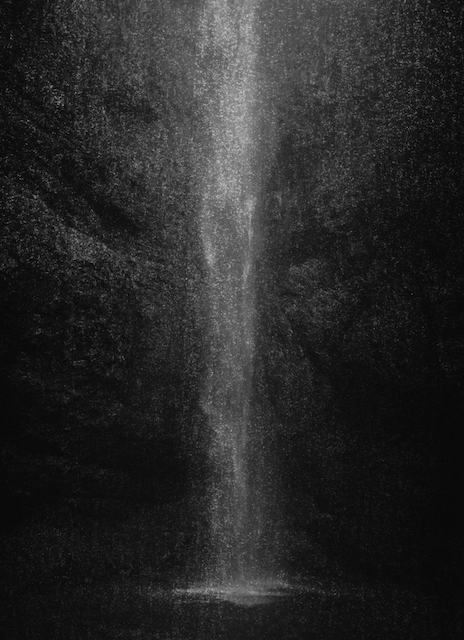

PF: Your works are basically kept in a neutral and restrained grayscale without emphasizing the strong contrast of black & white. Is there a special purpose behind this aesthetic?

Taca: The style I chose comes from two factors. Firstly, it comes from my aesthetic choices and personality. I consider myself rather nostalgic, with a sensible and calm nature. Secondly, it draws inspiration from my project, Odes. When I grew up and reread 2000-year-old Chinese poetry in a foreign land, I was able to appreciate the vanished civilizations that were encapsulated inside these old poems, as well as feel nostalgia for my own childhood. So, I deliberately went with a low-contrast tone. I hope that these works can evoke a subtle feeling similar to browsing through old images that have been lost in time.

© Taca Sui, The East Lake, from Chapter ‘The Journey of Wei Wan’, 2022. Courtesy of the artist & Three Shadows +3 Gallery (Beijing, Xiamen)

PF: Photography gives you access to the outside world and the freedom to create your own work. What is your understanding of the concept of freedom in the creative process and how do you maximize it visually?

Taca: In my recent project, I visited the earliest ritual sites of ancient Chinese civilization, even predating the concept of China itself. On the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival last year, I spent several hours on a hilltop, where our ancestors worshiped the moon thousands of years ago, eagerly awaiting the moon’s ascent to the mountaintop. At that moment, I suddenly felt that the environment resembled a small hill in a park near my home in New York —even the trees were similar.

It seemed to me that all of the things that were worshipped by ancient Chinese people, such as the sun, moon, sky, earth, and even the four seasons, are shared by everyone, everywhere. This led me to believe that the similarities in humankind’s culture and civilization outweigh our differences. And true freedom comes from confronting nature, feeling each individual’s existence, and breaking from all the constraints of any theories or ideologies.

© Taca Sui, The Lord of Yang, from Chapter ‘The Eight Lords of Qi State’, 2022. Courtesy of the artist & Three Shadows +3 Gallery (Beijing, Xiamen)

PF: Time is an important element in your work. What aspect of time do you wish to capture—the passing of time or its eternity?

Taca: In recent years, I’ve realized that I’ve been striving to capture a moment that blurs the boundary between past and present. Photography has the ability to transcend different times and spaces and serve as a bridge between them. So, the past and the present collide within a single shot, where they communicate and overlap like echoes. It dazzles the viewers for a brief moment. You will enjoy a similar feeling when you drive on a rural road at dusk. The view outside becomes distinct and yet familiar. The view might be entirely different simply because the light is slightly dimmer. This nuance is what draws me in.

© Taca Sui, The Oasis, from Chapter ‘The Journey of Wei Wan’, 2022. Courtesy of the artist & Three Shadows +3 Gallery (Beijing, Xiamen)

PF: Most of your earlier works were created as platinum and palladium prints, but for the Grotto Heavens series, you’ve opted for pigment prints. Why?

Taca: Grotto Heavens is a rather big project with several chapters. Those chapters follow a chronological order, starting from the origins and development of the concept of Grottos, then progressing towards its formation, and ultimately exploring its evolution. The majority of the chapters were shot on film and later presented as platinum and palladium prints.

© Taca Sui, Jiulong Mountain, from Chapter ‘The Immortal Land’, 2017. Courtesy of the artist & Three Shadows +3 Gallery (Beijing, Xiamen)

However, the second chapter, The Immortal Land, was captured using a digital back. This decision was made because the subject of this chapter is the cliffside tombs from the Western Han Dynasty, and I want to use a larger format to provide viewers with an immersive experience. Therefore, pigment printing was the only available option for presenting these photographs.

© Taca Sui, Cave in Kuocang Mountain, from Chapter ‘The Immortal Land’, 2017. Courtesy of the artist & Three Shadows +3 Gallery (Beijing, Xiamen)

PF: What kind of preparation do you usually do before shooting? What new projects do you have planned for the second part of the year?

Taca: Before projects, I normally spend some time reading and sorting the literature. In the second half of the year, I plan to continue with the Grotto Heavens project, and I will also take the opportunity to study the works of French archeologist, writer, and poet Victor Segalen, whom I have always been interested in.